Poetry, a Natural Thing

By Robert Duncan

The poem

feeds upon thought, feeling, impulse,

to breed itself,

a spiritual urgency at the dark ladders leaping.

From The Mystery of Things by Christopher Bollas pg 195:

What Rosenberg says of de Kooning, Leclaire of the psychoanalyst, and Vendler of the lyric poet, is evocative description, a conjuring of the nominated. Confronted with the impossible task of describing the mystery of things unconscious, these authors defy this fact and write anyway.

What things?

The things that live as effects, in the subjects who cultivate them, in the objects presumed to contain them, in the receivers assumed to know them not for what they are, but the familiar movement of the ‘are not’. Not the themes of life, the plots of the novel, the urgent reports of the analysand, but the forms of life.

What mystery?

An unanswerable, perhaps presiding question. What is the intelligence that moves through the mind to create its objects, to shapes its inscapes, to word itself, to gather moods, to effect the other’s arriving ideas, to… to… to…?

This is what I’ve been circling around for the last two weeks (in a vast procrastination exercise because I’m struggling to finish the book…) – I’ve been writing for years about ‘the feel of an idea’ as an occasion for articulation but what is the feel of the feel? There’s an arising in the psyche (what Freud called einfall: an idea falls into the mind) which we are capable of giving form to. I’ve been preoccupied by the form-giving itself but what about the encounter which precedes this? The otherness of what has fallen into the mind? It comes from some place other than our conscious, shaping, articulating mind. It’s not just a gift of language but rather something more intimate than that, something personal to us but in a real sense not from us. There is something which works through in the feel of the feel, as Wordsworth expresses in Tintern Abby:

And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man:

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things.

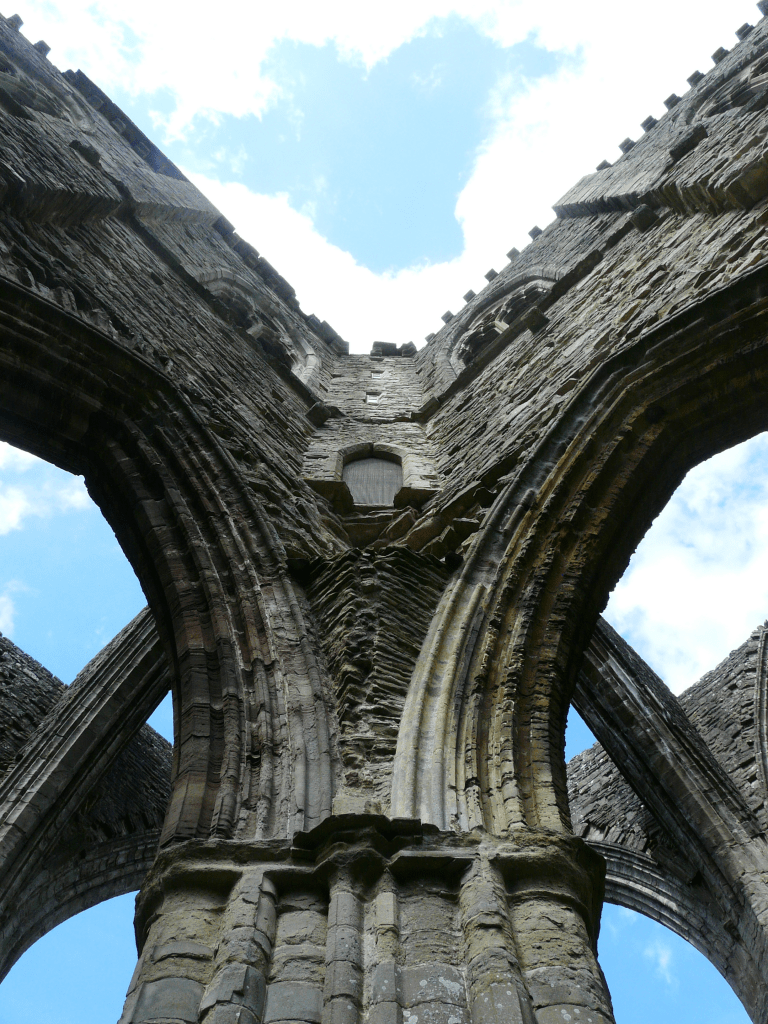

There’s something deeply human about this and yet, I think, not….? Seeing Tintern Abby through this lens reminds me of a scene I encountered in Bristol last summer. I was extremely pissed off with the world and upon seeing this wall I was suddenly filled with calm. I suspect scenes like this move me because they capture something of what exceeds form, something infinite still visible through the constraints of the form we create through and in response to it.

If we are, in Eliot’s sense, raiding the inarticulate then what is the inarticulate? What remains of it after we have made something articulate? The meshwork of the unconscious is part of this story, in the overwhelming range of sensory intensities which our psyche is constantly knitting together into dense thickets of latent meaning which we can barely grasp. But the materiality of how we give form is part of it as well, as Bollas notes on pg 173 of the Mystery of Things:

The term ‘transubstantial object’ allows me to think of the intrinsic integrity of the form into which one moves one’s sensibility in order to create: into musical thinking, prose thinking, painting thinking. These processes could be viewed in part as transformational objects in that each procedure will alter one’s internal life according to the laws of its own form. But a transubstantial object that receives, alters, and represents the sensibility of the subject who enters its terms and now lives within it.

We give form to objects, which constrain and enable that form in idiosyncratic ways. We give form in response to something which arises within us but which comes in a sense from outside us. But what is form? And what is it that remains formless?